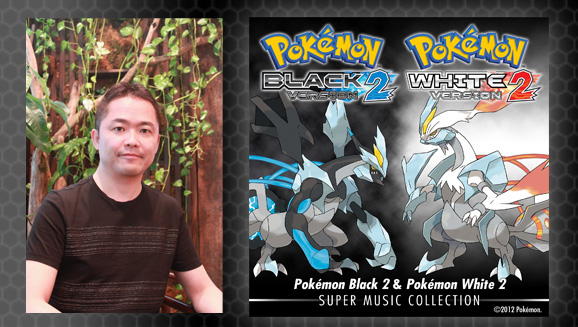

A Conversation with Pokémon’s Musical Maestro

Interview originally posted at: http://www.pokemon.com/us/pokemon-news/a-conversation-with-pokemons-musical-maestro/ on May 13th, 2014We talk to GAME FREAK original member Junichi Masuda about his role as Pokémon music composer, one of his many important contributions to the history of Pokémon games.

GAME FREAK’s Junichi Masuda is probably best known for his work as a game director, most recently on Pokémon X and Pokémon Y. But he began as, and continues to be, a gifted musical composer responsible for much of the iconic Pokémon game music that fans know by heart. To mark the launch of the Pokémon soundtracks on the iTunes Store, we had the opportunity to talk with Mr. Masuda about his more-than-20-year history with video game composition, his creative process, the production of the Pokémon game soundtracks, and much more.

Music has always been a part of Mr. Masuda’s life, even from an early age. His first memories of music stretch back to age 9, when he got a cassette player from his parents. “I first listened to rock and roll music. I’m not really sure who it was...it may have been American rock and roll. I just remember thinking it was really cool at the time,” he says.

Soon after, his interests turned closer to home when he developed an interest in the Japanese techno group Yellow Magic Orchestra, or YMO. The innovative group has made a big impression on musicians, including pop, hip hop, and house music performers, for nearly 40 years. It’s easy to see how Mr. Masuda found his way into video game composition—much of YMO’s music is very reminiscent of the sounds of early video games.

“YMO used a lot of synthesizers. I remember hearing the sound of those synthesizers for the first time and thinking it was so cool, and I really wanted to get one of my own. I took my parents with me to get my first synthesizer. It was a Korg MS-10, a really simple synth,” Mr. Masuda says. This first musical instrument provided him with a gateway into actually making music, or at least into understanding the sounds of music. “At first I really was just kind of copying the music I liked, like YMO, Ultravox, and the Human League,” Mr. Masuda says. “I’d be hanging out with friends and we’d try to copy the sounds that we heard. It probably was a few years later, when I was about 14, that I started to make my own songs.”

Like many musically inclined kids his age, Mr. Masuda joined his high-school band, where he played trombone. He also played synthesizer with a group of friends and composed songs for them to perform. Even with all that musical exposure, he didn’t really see a clear path to being a professional musician. “I knew I was interested in music, but I wanted to have it remain a hobby,” Mr. Masuda says.

Despite this early interest and acumen in music, Mr. Masuda’s attention moved away from that field and into another area that would guide his career path. “I knew how difficult to it was to make a living in the music industry, so that’s why I decided to go toward computer graphics and kept music as a hobby. Computer graphics were also a big emerging industry at the time, so after high school I went on to a technical school to study it,” Mr. Masuda says. The combination of musical talent and computer graphics training proved to be important skills for his entire career.

The drift away from his musical interests didn’t last long. At age 19, he met Pokémon creator Satoshi Tajiri, the man who would go on to found GAME FREAK. “Mr. Tajiri had started working on an NES game that was called Mendel Palace in the United States, and he asked me to make the music for the game. It sounded fun, and I was just a student at the time, so I decided to go for it,” Mr. Masuda says. He considers Mendel Palace a good first project for the way it wove the gameplay and music together. “When you moved, the music would play; when you stopped, the music stopped,” he explains.

Making music on video game systems in that day could be difficult, but Mr. Masuda relished the challenge. “Obviously there were a lot of limitations with the hardware and the number of sounds it could create,” Mr. Masuda says. “The NES had only three sound channels, so I would study a lot of three-voiced compositions, like those from Bach, and try to figure out how you could make that kind of music on the NES. Bach’s music sounds very beautiful without being complex. I really found the challenge of making music that would fit with games to be quite fascinating, and this feeling contributed to the start of my career.”

Mr. Masuda’s early experiences in game composition have stuck with him throughout his career. “I remember my earliest games like Mendel Palace. I’d listen to Stravinsky and it sounded heavy and cool, but the music in this game was a more lighthearted, fun-filled style. It was a challenge and something I learned a lot from,” he says. Another memorable game was Pulseman, which came out on the Sega Mega Drive (known in the United States as the Sega Genesis). “We went with more of a techno sound for the game, so it was a genre I had a lot of experience. Another unique aspect of that game was that the hardware featured a FM synthesizer, so I also had to do some programming work.”

The first Pokémon games presented challenges that were different from previous projects. The games were being developed simultaneously with the sounds and music, so Mr. Masuda had to imagine what a scene would sound like. “Sometimes I’d have a visual effect that I could match the music to, like the little falling sound before the battle begins. We also had to work on timing, such as making sure the music doesn’t start until the Trainer throws out his or her Poké Ball.”

Years of music composition for video games has given Mr. Masuda insight into the process. One of his most important lessons: listen to a lot of different music. “By the time I was about 20, I had over 1,000 CDs in a wide variety of genres—music from around the world, from traditional Japanese called gagaku, taiko music, Gamelan [traditional Indonesian ensemble music], European classical, rock, jazz, techno...and it all culminated into my own unique style,” he says. And plenty of classical music had influenced his compositions. Despite stating a preference for more traditional classical composers, he says he’s always been inspired by Stravinsky. “I was really into him, liked his work, like the Rite of Spring and the Firebird. A lot of people might find him too niche or avant garde compared to Bach or Mozart, for example. I read Stravinsky’s autobiography and musical scores, too.”

For Mr. Masuda, it’s also about finding your moment to be creative—it requires dedication and a little solitary confinement. “One of the important elements is that I have to be alone. Most of the time, when I’m with other people, I’m usually talking, so it’s kind of hard to hum a new song.” He laughs. “Also, when it comes to gameplay ideas and musical ideas, I find that I have to separate the two. I’ll choose whether today is a music day or a game design day, and focus my entire day on that aspect. I can’t think of both simultaneously. That focus is what’s important,” he explains. “On music days, I’ll find musical inspiration everywhere, including at work, waiting for the train, or even in the shower.”

One more lesson Mr. Masuda learned about video game composition came from cinema, but with a twist. “With movies, the music can match a scene perfectly and ramp up to reach a climactic moment along with the action. For games, it’s a little different, because the music doesn’t always play at the same locations for each person. You kind of have to imagine a lot of different scenarios and keep that in mind when you’re creating the songs,” he says. But that doesn’t mean you should ignore the scene—quite the opposite. “My advice would be to not just create songs, but really think about setting the scene and think about how you can influence the player’s experience regarding the gameplay along with the music.”

Composing music for video games has changed quite a bit since Mr. Masuda’s early days. The tools for creating music have improved significantly, and his approach has changed, too. His experience working on virtually every Pokémon game has certainly opened up more avenues for creativity. “Nowadays it’s more that we come up with the music first because we kind of already know what is in a Pokémon game...we know what the scenes are like. I’ll come up with songs that fit the known quantities that we already have,” Mr. Masuda says.

But that doesn’t mean the work has become easier. “Obviously there’s a lot more freedom when composing game music these days, but that comes with a lot of challenges. You can do a lot more, but you also have to do a lot more,” he says. “For all the freedom we have now, I think it’s a good time for all of us game music composers to step back and really think about what game music should be. Interactivity is an element in games that you don’t find elsewhere. And with that in mind, maybe we should think about what we’re doing with game music.”

A Survey of the History of Pokémon Music

The development and mastering of the Pokémon soundtracks has given Mr. Masuda a chance to reflect on the creation of his long legacy of musical composition. We go through the chronology of major Pokémon games to get his insight into them. The team responsible for remastering all the soundtracks spent considerable time adjusting the music so it would sound good regardless of where the listener was, whether in the car or listening to a home stereo.Mr. Masuda’s role in the music and sounds of the original Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue games can’t be understated. “We’d write music directly on the Game Boy using a special device. For those games, I wrote all the songs and created all the Pokémon cries. I was definitely able to pour everything I had into those sounds,” he explains. Because of the primitive graphics of the original Game Boy, the music served a greater role in setting the mood and indicating where the player was in the game. “When I listen to this soundtrack, I hear things that I’d like to go back and fix and make changes to, but the majority I really like. I’ll listen and think, ‘Wow, this is really good. I can’t believe I made this!’” Mr. Masuda laughs.

For Mr. Masuda, the primary focus as composer changed with the launch of Pokémon Gold and Pokémon Silver. He became more involved as both a programmer and a game director. And it was the first time that Gō Ichinose joined GAME FREAK’s sound department. With the extra help and the familiar environment, the team was able to create new songs very quickly and early in development.

Things changed with Pokémon Ruby and Pokémon Sapphire and the migration to the Game Boy Advance. Mr. Masuda explains, “We were able to sample the sounds before adding it to the hardware, which was really nice, but it was more work and took more time to figure out the process.” In the end they were also able to think more about the tone of the music thanks to the wider sound range of the new hardware, including the timpani drum. “It was another sound I discovered at the time...that we used a lot in Pokémon Ruby and Pokémon Sapphire.”

The knowledge gleaned from Pokémon Ruby and Pokémon Sapphire could be applied efficiently to Pokémon FireRed and Pokémon LeafGreen. Although Mr. Masuda had created the majority of the original compositions, it was mostly Mr. Ichinose who updated the music. “We spent a lot of time making sure that anyone could play these games, so we didn’t go too far with new gameplay elements or go too far out there. In that spirit, we took the original songs and added elements to it without changing it too much,” Mr. Masuda says.

Pokémon Diamond and Pokémon Pearl proved to be something of a turning point for the music of Pokémon games. By this time, a lot of Pokémon music had been produced, and the “Pokémon sound” had been well established. Plus, the new Nintendo DS hardware once again provided a new palette of sounds to create from. “I wanted to try to really expand what really represents Pokémon,” says Mr. Masuda. “I had some room with the music to experiment on what was previously considered Pokémon music.” He attributes much of this experimentation to having a set look for Pokémon games. With that in place, he knew he could try new ideas without alienating the player.

The musical updating for Pokémon HeartGold and Pokémon SoulSilver was yet another big jump in hardware using the sounds of a previous game. For this title, Mr. Masuda left the production work mostly in the capable hands of GAME FREAK composers Mr. Ichinose and Shota Kageyama. Their goal was to make sure that both new players and the Pokémon fans who remembered playing Pokémon Gold and Pokémon Silver were equally satisfied. “One thing we really kept in mind is that those who played the original Pokémon Gold and Pokémon Silver would notice if we changed the songs, and we wanted to preserve their memories of the games,” Mr. Masuda says.

Pokémon Black and Pokémon White were the first games to be inspired by a region outside of Japan, namely New York City. “We were really aiming for a ‘cool’ feel, which was a different direction for the Pokémon series. We also wanted new musical challenges. We had some more new members in the music team, so we asked each one to try a different musical genre. I remained the composer for battles and such, where we tried to stick with traditional Pokémon music.” It fit into the concept of the Unova region, where there were many different perspectives in the game, but it could also be viewed as one large world.

Players returned to Unova nearly two years later with Pokémon Black 2 and Pokémon White 2, and that passage of time was also reflected in the in-game setting. The music team seized upon that notion and ran with it. “The setting in these games being two years later after Pokémon Black and Pokémon White, we tried to think about what had changed. We took everything we heard in Pokémon Black and Pokémon White and we tried to update it to sound as it would two years later,” Mr. Masuda says.

The scenes and motifs of Pokémon X and Pokémon Y were even more explicitly based on the country of France, but that didn’t necessarily carry over into the music. On the contrary, it’s something they tried to avoid. “If one of the areas looks very European, and the music matches, then it’s too much like Europe. We used the music to differentiate it a little bit,” Mr. Masuda explains. Instead, the team focused on using the music to influence the players’ feelings and emotions—should a player feel at ease, or is there tension in the action that the music can convey? “That’s more the primary thing when we’re developing the music,” Mr. Masuda says.

Mr. Masuda’s place in the pantheon of video games as a composer and game director has already been set. With insight into his passion for music and Pokémon, we look forward to many more years of developing the games—and music—that Pokémon fans love.

This page has been viewed 9705 times.

Last updated 09 Nov 2017 23:36

by Sunain.

Revision #6

Revision #6